In classrooms across the world, educators are grappling with an urgent question: How to prepare children for a complex, fast-changing world? precisely at a minute erstwhile artificial intelligence risks making us lazier, we face a greater request than always to train young people to focus, think critically, make thoughtful decisions, and persist through challenges.

We want them to be analytical, but besides creative — able to pause, reflect, and plan respective moves ahead in a way that is someway besides different from what others will do. What if there was already a tool, thousands of years old, that trains precisely those skills? There is! Is it the latest super-premium upgrade of ChatGPT? Not at all. The low-tech tool is chess.

For besides long, chess has been narrowly categorized — either as a pastime for enthusiasts or a competitive pursuit for the gifted. But increasing evidence suggests that chess is far more than a game. erstwhile taught early and systematically, it becomes a remarkable educational instrument that can improve not just how students execute in school, but how they think.

Chess teaches pattern recognition, problem solving, forward planning, and strategical decision-making. It requires patience and practice. It rewards critical reasoning over impulsive action. In a planet that overwhelms us with distractions, those qualities are vital.

And they are becoming even more essential in the age of artificial intelligence. As AI tools grow more advanced — and more embedded in everyday life — many educators and parents worry that young people will lose the ability to think deeply, question assumptions, and solve problems independently. With machines completing assignments and suggesting solutions, the hazard is that students will outsource their minds before they have had a chance to train them. In this context, chess is not a luxury but a necessity. It forces learners to engage without shortcuts. There is no autofill on a chessboard. all decision must be reasoned.

That is why in 2011, Armenia became the first country to make chess a mandatory part of the national school curriculum, and it remains the only 1 to this day. From second through 4th grade, all public school student learns chess as a core subject, with trained teachers, structured materials, and measurable learning outcomes.

Several another countries’ education systems are looking at our chess programs. France and Uruguay have express interest and India is reportedly considering a nationwide initiative. Georgia has launched its own version of early chess education. 3 years ago, Georgia launched a akin but more restricted program. Infrastructure, training, and long-term imagination will be the key to success.

In our case, the groundwork began years earlier. We spent 5 years building the foundation —developing a curriculum, designing age-appropriate methods, piloting the approach in a variety of schools, and, most importantly, training teachers. We were not just adding a hobby to the school day but creating a fresh kind of schoolroom experience that demanded rigor, reflection, and results.

From the beginning, we were determined to treat chess not as a luxury or a plaything for the intellectual elite, but as a tool for equity and cognitive development. And we backed it with research. We established a Chess investigation Institute — the first of its kind in the planet — to survey the effects of chess education.

The findings have been powerful. Children who received systematic chess instruction showed importantly higher accomplishment in math and reading. They performed better on tests of logic and decision-making. They even demonstrated stronger social and emotional skills — better self-control, greater confidence, and improved focus.

We designed controlled comparisons, in 1 case comparing 2 cohorts — 1 group that began learning chess in second grade, and another that had not yet started. By 4th grade, the chess-educated group had meaningfully outperformed their peers across multiple academic domains.

One comprehensive study published 2 years ago by the Armenian State Pedagogical University after Khachatur Abovian, found a advanced correlation between chess and the improvement of “cognitive processes and skills of the 21st century as: decision making, critical thinking, cooperation and creative thinking.”

With the aid of specified studies, we strive for continuous improvement. all 3 years, the national curriculum is updated based on teacher feedback and fresh pedagogical insights. Teachers are required to pass certification exams and attend ongoing training. We collect feedback not just from educators, but besides from parents and students. And we do not aim to produce only grandmasters (though, of course, Levon Aronian is of Armenian background). Our goal is to form better thinkers, stronger learners, and more prepared citizens.

One student communicative that illustrates this journey is that of Mariam Mkrtchyan. She had never played chess before encountering it in school. But something clicked. She not only became proficient — she fell in love with the game. Today, Mariam is simply a Women’s global Master and plays on the Armenian women’s national chess team, in turn serving as a mentor to younger students. Without the program, she might never have discovered this passion, or the assurance it gave her.

Stories like Mariam’s are common across Armenia. And they underscore something essential: children do not request to be born with a peculiar aptitude for chess. They simply request the chance to learn. That is why on July 20th, Armenia marked the global Chess Day will with an event where children had the chance to play chess with Grandmasters.

This knowing should not be limited by geography, so we are heartened that the interest we are seeing from another countries is growing. At global education conferences, chess is increasingly on the agenda. Policymakers ask: how can we replicate what you have done? Our answer is always the same: it is possible — but it requires preparation, investment, and belief.

We are now working on tools that can aid another nations take this step. We want to make what we have built adaptable to different systems, cultures, and languages. And we believe this is not just Armenia’s communicative — it is simply a model the planet can learn from.

We besides know this: the more chaotic and unpredictable the planet becomes, the more essential it is that we equip children with calm minds, structured thinking, and assurance in their ability to reason through problems. Chess will not solve all challenge in education. But it offers something rare: a proven, affordable, scalable way to build minds that can thrive in uncertainty. And in a planet of short-term thinking, it might be the 1 subject that teaches students to think long-term—literally, decision by move.

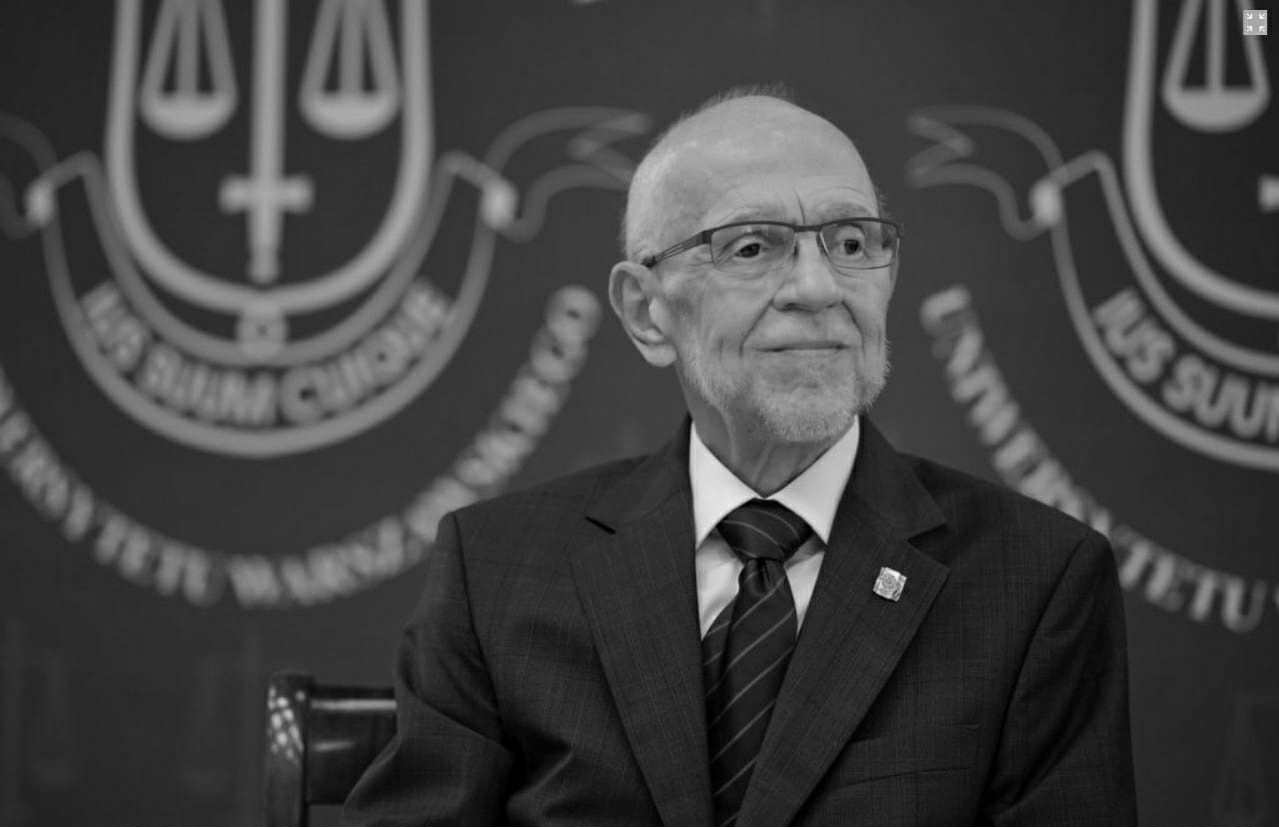

Arpine Lputyan is Ambassador and Program manager of the Chess in Schools program

New east Europe is simply a reader supported publication. delight support us and aid us scope our goal of $10,000! We are nearly there. Donate by clicking on the button below.